After reading it, I’d like to think doing nothing is not an option

By Bob McKenzie

So, now what?

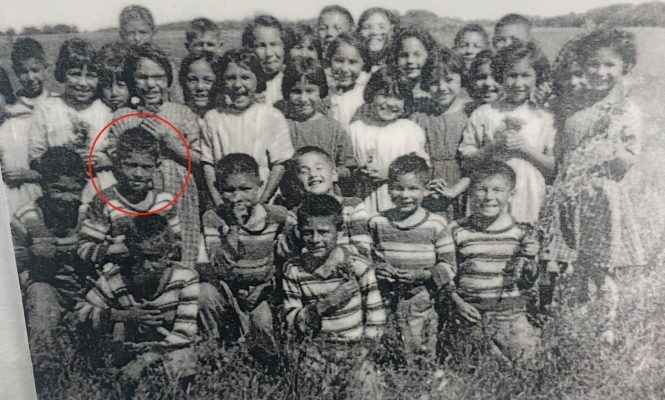

You have read Eugene Arcand’s story that appeared on tsn.ca over the past five days.

Perhaps you’re still trying to process how it happened in a country that fancies itself a civilized society. Maybe you’re wondering what you can do to help in the glacially paced saga that is the response to the Truth, Reconciliation and Calls to Action.

Because, after reading Eugene’s story, I’d like to think doing nothing is not an option.

But how exactly do we go about that? And how do we go about it in such a way as to not just try to make ourselves feel good about a symbolic gesture — putting on an #EveryChildMatters orange shirt every Sept. 30, for example — but doing so in a manner that actually might help make a real difference?

I guess what you’re asking is how do you understand an important story like the one Eugene told? How can we understand his story, and others like it, and then take real action?

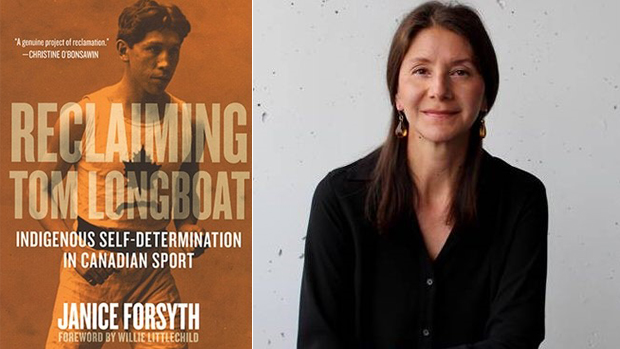

says Dr. Janice Forsyth, who has a PhD in sport history and is an associate professor in the School of Kinesiology at the University of British Columbia.

Forsyth, a member of the Fisher River Cree Nation in Manitoba, describes herself as a historical sociologist who works with different concepts of power to explore the relationship between sport and culture from Indigenous points of view.

She focuses on the way organized sports have been used as tools for colonization,

and how Indigenous people use those same activities for cultural regeneration and survival.

Eugene’s story is one of many stories that show us what colonization looks like, especially where racism is concerned,

Forsyth said. What’s important to remember, too, is that his story is not the definitive story — and that is what Eugene is trying to say — but his story, like others, have become an important entry point for helping us to understand Residential School history and its complex legacy.

Forsyth said spending time to gain a deeper understanding of that history and colonialism is crucial before taking action. She also acknowledges that the understanding

part can be daunting. It’s such a weighty issue, with voluminous amounts of information. It can be overwhelming.

The Truth and Reconciliation Report, you have to point to that, but it is intimidating,

Forsyth said. It’s thousands of pages long. A lot of people who want to understand the issue and take action don’t know where to go to find information that’s helpful and digestible.

Well, the first place to start is the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba or, more specifically, its website.

It has a wealth of digestible information and documentation on the past, present and future, including all the official reports (Truth and Reconciliation and Calls to Action, amongst so many others). The website really is an incredible resource.

Forsyth has written a lot on all these issues, too. Simply do a Google search: Residential Schools, Janice Forsyth and any or all of sports or hockey or assimilation or colonialism. A lot of her work will appear. She is also the author of an award-winning book — Reclaiming Tom Longboat: Indigenous Self-Determination in Canadian Sport.

Here is a link to an excerpt from that work that focuses on Longboat himself.

Here is another link to an excerpt from that work that focuses on residential schools.

I would also highly recommend you read Fred Sasakamoose’s book, Call Me Indian: From the Trauma of Residential School to Becoming the NHL’s First Treaty Indigenous Player.

We live in a culture where many people want to do something right away, which is a good thing because we need public support to facilitate change, but it also can create problems,

Forsyth said. When people move too fast and don’t think about the steps they take, they can inadvertently take the wrong steps. So, if they move a little slower, take time to learn and listen, and talk to each other, build relationships and figure out what works best for the injured party, then we are all in a much better position to do meaningful work.

Eugene doesn’t mind if someone takes a well-intentioned wrong step

in the name of reconciliation and call to action.

Wrong steps can sometimes lead us to the right steps,

he said. The key is to take a step. Taking no steps, doing nothing, that’s the real problem.

There’s no easy or one size fits all suggestion for how we Canadians can personally advance the cause of Truth, Reconciliation and Calls to Action. But a good start would be to review all 94 Calls to Action. And since this story has been set against the backdrop of hockey, perhaps you might want to focus on Nos. 87 through 91 that deal with Indigenous sport. To wit:

- We call upon all levels of government, in collaboration with Aboriginal peoples, sports halls of fame, and other relevant organizations, to provide public education that tells the national story of Aboriginal athletes in history.

- We call upon all levels of government to take action to ensure long-term Aboriginal athlete development and growth, and continued support for the North American Indigenous Games, including funding to host the games and for provincial and territorial team preparation and travel.

- We call upon the federal government to amend the Physical Activity and Sport Act to support reconciliation by ensuring that policies to promote physical activity as a fundamental element of health and well-being, reduce barriers to sports participation, increase the pursuit of excellence in sport, and build capacity in the Canadian sport system, are inclusive of Aboriginal peoples.

- We call upon the federal government to ensure that national sports policies, programs, and initiatives are inclusive of Aboriginal peoples, including, but not limited to, establishing:

- In collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, stable funding for, and access to, community sports programs that reflect the diverse cultures and traditional sporting activities of Aboriginal peoples.

- An elite athlete development program for Aboriginal athletes.

- Programs for coaches, trainers, and sports officials that are culturally relevant for Aboriginal peoples. iv. Anti-racism awareness and training programs.

- We call upon the officials and host countries of international sporting events such as the Olympics, Pan Am, and Commonwealth games to ensure that Indigenous peoples’ territorial protocols are respected, and local Indigenous communities are engaged in all aspects of planning and participating in such events.

While those Calls implore government

to take the action, is there not something there that you could contribute to in some fashion?

Because here’s what I believe I’ve learned above all else from Eugene’s story. Canada tried to systematically erase Indigenous culture and in doing so severely damaged that culture and its people. The path forward for those people, and the culture, is to do everything possible to re-establish the culture.

So, anything you or I can do to assist in that endeavour may be helpful.

Forsyth believes social media can be a powerful platform to support change, that the Aboriginal Sport Circle, the National Aboriginal Hockey Championships, the Little NHL and the North American Indigenous Games are some of the many Indigenous organizations and events that could benefit from having a higher profile – and greater financial support, too.

Let’s be hopeful and acknowledge change is happening,

Forsyth said. It’s not happening as fast as we would like. But every day, more individuals learn [about the issues] and speak out. We are getting more forward thinkers who want to help. We’re just trying to not hurt people any more, to always have that ethic of care.

The final word goes to Eugene Arcand, 781.

I don’t have any one answer [on what a person can do to help],

Eugene said. But if that person takes the step of a Call to Action to make a change in their own life, to try to better understand the First People of this country, and the reasons why we are mired in poverty and this hell of life, well, we welcome them to do that so we can better advance some level of comfort in our own lands.